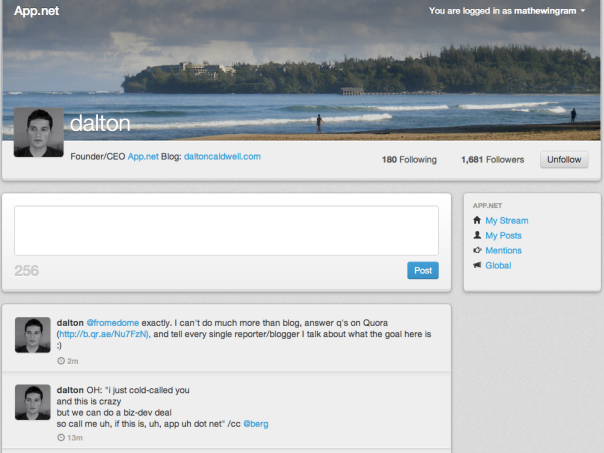

Much of the coverage of App.net — the ambitious project from entrepreneur Dalton Caldwell that just finished raising $ 500,000 through a Kickstarter-like crowdfunding campaign — has focused on the idea that Caldwell is building a “paid version of Twitter.” That has led a number of critics to complain that no one wants an alternative to Twitter and therefore App.net will almost certainly fail. But whether it succeeds or not, the idea behind the venture is actually much bigger than just building a paid Twitter clone. What Caldwell wants to do is create what he and others think Twitter could have been before it decided to become a global media entity: namely, a unified message bus for the social web, or a way of tying together multiple apps and services into a single real-time information delivery system.

This is a much more ambitious goal than just cloning Twitter or duplicating some of its features. And while Caldwell has beaten many people’s expectations by even getting funded in the first place, it remains to be seen whether enough users and developers will be willing to pay for the service to make it an effective resource — especially since other similar efforts to create an open ecosystem for the social web have mostly failed. Are there enough supporters of an open standard to make a difference, or is the social web doomed to be a world of competing proprietary walled gardens?

App.net wants to be a platform, not just an app

Orian Marx, the creator of New York-based startup Siftee, does a good job in a recent post of describing the difference between what the alpha version of App.net looks like now and the broader ambitions of Caldwell and his partners. What you see when you go to the site appears to be a very stripped-down version of Twitter, but with far fewer users and features, and that has led many to dismiss it as a short-lived clone — one that will die because it won’t be able to compete with the kind of network effects Twitter has developed (although Caldwell argues network effects can be a negative as well as a positive). As Marx describes it:

“App.net will combine the simplicity of cloud infrastructure with the power of web frameworks to deliver the best platform for developing social web applications.”

In other words, the alpha is more like a test case or prototype of what could be built by using the platform App.net is trying to construct — one that uses open standards such as PubSubHubbub and ActivityStreams and other protocols that make it easy to distribute information through multiple networks, as well as allowing users to find and “follow” other users, and other things that we associated with Twitter or social networking in general. One comparison would be to Amazon Web Services, which is a collection of tools like the Elastic Compute Cloud or EC2 that developers and companies can use to build services on top of.

Another way of thinking about what App.net is trying to do is to think about what email used to look like, or (for those who aren’t quite as old) what instant messaging used to be like. There were competing platforms and competing standards, and nothing like an open API or any of the other things we associate with allowing different services to exchange information. Users of CompuServe Mail couldn’t easily send mail to other mail-hosting services, and later on users of ICQ or AOL’s Instant Messenger couldn’t easily chat with users of other competing platforms such as Microsoft’s MSN or Google’s GChat.

As Albert Wenger of Union Square Ventures notes in a recent post about the potential benefits of App.net, what the social web is lacking is a way of tying together various standards and protocols that allow anyone to integrate or exchange information easily with any other similar service — in the same way that anyone can send email to anyone else on the internet:

“It would a huge benefit to society if we can get with social networking to where we are with email today: it is fundamentally decentralized with nobody controlling who can email whom about what, anyone can use email essentially for free, there are opensource and commercial implementations available and third parties are offering value added services.”

Will the promise of an open platform be enough?

While Twitter has become a powerful information-publishing system and a kind of real-time newswire, it is still a private corporation with its own commercial interests, and as it expands its attempts to control more of its network — in order to monetize it more effectively — it is clamping down on the use of its API in ways that have caused friction with both developers and users. Much of the impetus for Caldwell’s project came from that dissatisfaction, and the feeling that Twitter at some point gave up on its desire to be an information utility and chose to become an advertising-based media entity instead. As one App.net supporter put it:

“[App.net] provides a solid API platform that is less likely to be yanked out from under our feet when the VCs get antsy and want to see a profit or acquisition.”

There have been other efforts to create a kind of open platform for the social web, however, and most have not ended well: one was an attempt to create a public standard for social connections called OpenSocial, which was driven by Google but designed to be an open protocol. Although the project still exists, it made very little headway, and was more or less doomed when Google recently killed off its Social Graph API. Rightly or wrongly, the project was seen as Google’s attempt to compete with Facebook — but its efforts have since been diverted to promoting its own Google+ network (which ironically still doesn’t have a fully open API of its own).

In some ways, Caldwell’s App.net also has similarities to FriendFeed, the federated social network that former Google staffers Bret Taylor and Paul Buchheit (one of the original developers of Gmail) created in 2007, which allowed users to pull in messages and updates from multiple networks such as Twitter, Facebook and Flickr. FriendFeed was eventually acquired by Facebook in 2009 for $ 48 million and Taylor became the company’s chief operating officer and one of the architects of its market-dominating “open graph platform.”

Will App.net ultimately wind up on the scrap heap along with other attempts to create an open social ecosystem, a victim of the market power of incumbents like Facebook and Twitter and/or the ambivalence of users? Or will it gain enough support to become a real alternative to the walled gardens that currently make up the social web?

Post and thumbnail images courtesy of Flickr users Rosaura Ochoa and See-ming Lee

![]()